The movie Titanic begins with an elderly Rose telling the story of her voyage across the Atlantic. As we push in on her eyes, we suddenly find ourselves in 1912, and the movie begins in earnest. Only a few times during the film do we return to the elderly Rose to touch in on her experience—but the movie ends there, just as it began. In storytelling, this is known as a framing device: a story told within the context of another story. Framing devices can be very simple, or very complex, as we’ll see in a moment. In every case, the framing device is a gateway that sets the stage for a deeper journey into story.

Framing devices have been around for as long as stories themselves. Many of the earliest recorded stories—such as The Ramayana, The Mahabharta, and The Odyssey—were told by an in-book narrator. Frame stories glue together collections such as The Canterbury Tales and the Arabian Nights, and set the stage for comparatively recent tales such as Wuthering Heights. Shakespeare used a “play within a play” to imply that Hamlet knew of his uncle’s murderous guilt. Framing devices appear in modern literature as well—such as in Patrick Rothfuss’ mega-popular The Name of the Wind, in which Kvothe tells stories from his past even as new events unfold in his present.

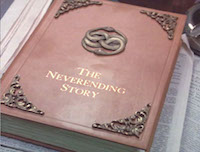

Naturally, framing devices have found their way into movies and TV shows as well. Classic films with framing devices include The Princess Bride (told by Peter Falk to Fred Savage, with the narrative reversing and changing course when the two characters disagree on the tale’s direction), and The Neverending Story (a book within a movie, the twist being that the main character “enters” the book). More recent films with framing devices include Life of Pi (a white lie told to a journalist) and Slumdog Millionaire (a confession at a police station). On TV, How I Met Your Mother has a framing device implied by the title, and LOST featured a unique structure that included flashbacks, flash forwards, and flashes in other directions in almost every episode. These are just examples; dozens of shows and movies use similar devices. Framing devices are absolutely everywhere.

But where frame stories get really interesting is when they start being stacked up: stories within stories within stories. One of the best examples is the eighth volume of Neil Gaiman’s The Sandman (which I recently discussed at length), entitled “World’s End.” Modeled after The Canterbury Tales, this story features a group of travelers trapped at an inn between worlds, going around a table telling stories. The storytelling peaks with the issue “Cerements,” in which the character of Petrefax tells the tale of a sky burial at which several corpse-handlers sit around telling stories of their own. One of those stories is the tale of a student’s apprenticeship to the Mistress Veltis, who in the story tells her own story about how she lost her hand to a magic book. You follow all that? That’s four layers of nested storytelling—all within the greater story arc of the Dream King.

Another great example is Inception, in which Leonardo DiCaprio enters Cillian Murphy’s dream to implant an idea in his subconscious. In the dream, DiCaprio puts Murphy to sleep, following him into a second layer of dreaming which soon gives way to a third—the catch being that time passes ever slower within each nested dream. In the innermost dream, Leo gets knocked out and enters “limbo”—an endless dream that could conceivably last for eternity while only seconds pass in the real world. After what seems like years, Leonardo finally wakes through each successive dream layer, returning (we think) to his real, waking life. For those keeping score, that’s five layers of nested story.

As an aside: Christopher Nolan may have been inspired by two classic episodes of Star Trek: The Next Generation that both involve frame stories. In “Frame of Mind,” Commander Riker finds himself performing in a play in which he’s a patient in a psych ward—only, the ward becomes real, and his doctors tell him he’s crazy. At the episode’s climax, reality shatters, and Riker discovers he was trapped in a dream within a dream. In “The Inner Light,” Captain Picard gets zapped by a satellite and lives forty years of another man’s life on a faraway planet. He becomes a father and a grandfather and ultimately forgets his old life—until, as he lay dying, the entire experience is revealed as a kind of experiential history book. When he finally wakes up, only forty-five minutes have passed on the Enterprise. Both of these episodes feature framing device motifs that show up in Inception.

As an aside: Christopher Nolan may have been inspired by two classic episodes of Star Trek: The Next Generation that both involve frame stories. In “Frame of Mind,” Commander Riker finds himself performing in a play in which he’s a patient in a psych ward—only, the ward becomes real, and his doctors tell him he’s crazy. At the episode’s climax, reality shatters, and Riker discovers he was trapped in a dream within a dream. In “The Inner Light,” Captain Picard gets zapped by a satellite and lives forty years of another man’s life on a faraway planet. He becomes a father and a grandfather and ultimately forgets his old life—until, as he lay dying, the entire experience is revealed as a kind of experiential history book. When he finally wakes up, only forty-five minutes have passed on the Enterprise. Both of these episodes feature framing device motifs that show up in Inception.

In David Mitchell’s Cloud Atlas, six different tales are nested inside each other like Russian dolls (This is not true of the movie adaptation, which I recently reviewed.) The first is “The Pacific Journal of Adam Ewing,” in which the main character embarks on a journey across the Pacific in 1850. The author cuts the story off halfway (literally midsentence!) to begin a second tale, this one set in 1931 and following the character of Robert Frobisher—who, it turns out, is reading Ewing’s journal. Frobisher’s tale is itself cut off to begin a story set in 1975—and onward it goes, each new story set further in the future, each new character reading the text of the previous tale. Only once the sixth story concludes does Mitchell unwind it all, telling the second half of each tale in reverse chronological order and ending where it all began. At six layers deep, Cloud Atlas might just be the most complex framing device ever created. (If it’s not, I’d love to know what is…)

These examples are complex, but they raise a simple question: why do framing devices work so well? Perhaps it has to do with the simple idea of suspension of disbelief. As readers and viewers, we have to suspend our knowledge that fiction is fake when we read a book or see a movie. That’s how we’re able to “get into” the experience. But when we experience a story within a story, that transition is more natural. It’s as if once we make that first leap of the imagination, we get more easily swept away with each new layer.

And when it all ends… we find ourselves back in the first frame, often surprised to remember where it all began. That moment can be powerful, and speaks to the intoxicating power of a well-told story. Perhaps that’s why framing devices have been around for as long as stories themselves.

And when it all ends… we find ourselves back in the first frame, often surprised to remember where it all began. That moment can be powerful, and speaks to the intoxicating power of a well-told story. Perhaps that’s why framing devices have been around for as long as stories themselves.

Anyway, that’s a brief look at stories within stories within stories. Next week we’ll take the whole thing interactive and explore some games within games within games. Stay tuned…

Brad Kane writes for and about the entertainment industry, focusing on storytelling in movies, TV, games, and more. If you enjoyed this article, you can follow him on Twitter, like Story Worlds on Facebook, or check out his website which archives the Story Worlds series.